Wellbeing in the university landscape

by James RedmanFor prospective university students, the choice of a healthy living environment has become part of the application process. Mental wellbeing is no longer considered secondary to physical health. Prospective students are now looking for a living environment that feels welcoming, flexible and healthy, and universities are responding through the development and management of their estates.

COVID-19 has further highlighted the role of wellbeing. Lockdown has limited our ability to interact socially, access outdoor spaces and continue our old routines. Students have faced school closures and uncertainty over the reopening of universities. There are concerns over the long-term mental health impact of lockdown, which for some has resulted in stress, anxiety, loneliness and a drop in confidence.

University of York. Photograph Polly Tootal.

View over the campus lake, University of York. Photograph Polly Tootal.

But lockdown has presented opportunities as well. It has been a unique moment in time to hit the ‘pause’ button, to give individuals and organisations the chance to reflect and quickly implement cultural changes that were originally been part of a longer-term agenda. Ten-year plans have been turned around in a matter of weeks, something that was previously thought impossible. Switching to online teaching, for example, has been part of many universities’ long-term plans, but COVID-19 accelerated this out of necessity. And so we can now justifiably take the time and care to think about a positive future for all generations. We have been rudely stripped of our old normal, yet we are now in control of what the new normal can be – a future that places our wellbeing at the centre of our lives.

“The university of the future will be shaped less by rigid teaching methods and more by experiences, community, social interaction and collaboration.”

Universities are rethinking what constitutes their campus of the future, creating environments that are inviting, healthy and flexible and represent good value for money for students paying up to £9,000 a year in tuition fees. Their choices will span the campus landscape and built environment at large, along with transportation options and living conditions. With online teaching now embedded, the university of the future will be shaped less by rigid teaching methods and more by experiences, community, social interaction and collaboration.

In recent years, researchers have demonstrated that access to green space can reduce your risk of mental health problems, improve your mood and increase your life satisfaction. Harnessing the potential of green campuses is important for maximising students’ wellbeing. Making outdoor spaces readily accessible and maintaining them to a high standard allows students and staff to have a visual and physical connection to nature, and is essential to a balanced and healthy life. Perhaps we will see more student-run gardens – spaces for growing fruit and vegetables, a place to meet, get fresh air, contemplate, pause. Or perhaps there will be more outdoor gyms and exercise routes, where landscape and community connect.

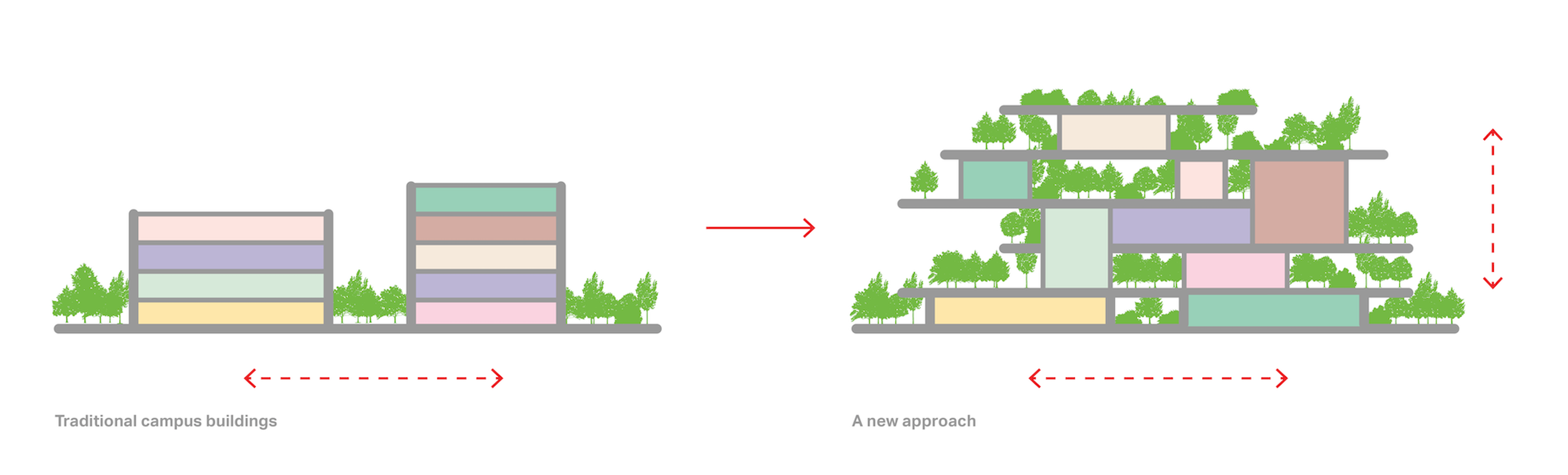

A strong connection to nature is likely to be even more prevalent within future building design as well. The notion of biophilic design – where building occupants are connected with nature – can reduce stress, improve cognitive function, and enhance mood and creativity. At Make we place these themes at the very centre of higher education building design. Historically, building design has turned its back on the natural environment, the facade forming a barrier between nature and artifice. Yet the higher education buildings of the future may well introduce landscaping at all levels, with external terraces, planting, vertical gardens and natural materials creating a three-dimensional campus. Such buildings will be naturally ventilated and maximise natural light during the day – a piece of architectural therapy, if you will.

Higher education building design should also promote wellbeing through its composition, function and spatial arrangement, much like contemporary office design. The notion of a normal, or standardised, workplace now appears defunct. Buildings should seek to offer freedom to their occupants, recognising that everyone is different and one person’s optimal working environment might be another’s worst nightmare. All working environments should feel welcoming, flexible and safe. Choice is key here – how do we design for introverts and extroverts? How can we create buildings that foster social interaction and creative dialogue while also providing a sanctuary for quiet work? How can we make buildings accessible to all, both day and night? University campuses must work hard around the clock, helping students forge individual routines within their ideal work and social environment.

Prospective students will need to see that higher education buildings support and sustain their occupants on a daily basis – for example, through healthy food and drink options, a variety of workspaces and environments, adjustable workstations, movable furniture, excellent technology, cleanliness, and considered lighting. The campus should be a site for positive placemaking, which can be achieved through safe and sustainable transport, generous cycle storage, pedestrian-friendly areas, inspiring public art, and events for and by the students. A positive university brand will enable them to feel part of a wider community that they can lean on, integrate into and ultimately be proud of.

“The sector faces increasing demand from students and academics for more diverse spaces to meet, study and socialise.”

We are in the midst of substantial cultural change. A global tragedy has created a unique scenario in which we have all been affected by the same event. Together we are back at the start line, reflecting on a pre-COVID world but with the opportunity to determine what our future looks like. This will shape the way we live and work for generations to come. We may never get a chance like this again, and so it is our duty to up the ante on how we design spaces, places and buildings to ensure every individual’s wellbeing is at the heart of the design. Together we should be shaping the most positive, supportive and fulfilling experiences for all, in turn setting the benchmark for living, working and socialising.

Authors

James Redman is head of Make's urban design working group. He's currently leading several strategic masterplanning projects, including the masterplan for Swindon's Kimmerfields regeneration scheme.

Publication

This article appeared in Exchange Issue No. 3, a look at how the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced the future of university design, featuring insight from chancellors, architects, students and more.

Read more