Ask the Makers

by Emma Thomas, Liam Bonnar, Greg Willis and Jennifer SoPage contents

Many of our interviewees for our higher education Exchange publication spoke about the need to integrate campuses within cities, increase building stock flexibility for sustainability and respond to restricted budgets. We asked some of our architects at Make to offer their insights on these themes. Emma Thomas, Greg Willis, Liam Bonnar and Jennifer So have experience on university projects across the UK and Australia – here’s what they had to say.

Flexibility in design

How can universities design in flexibility to respond to changes in course popularity and the way students are taught?

Emma Thomas

A building’s fabric often outlives the original functional requirements, as user needs change over time faster than our building stock. Most recently, in higher education this has been in the form of a gradual shift from demand for traditional lecture theatres to individual and group learning spaces as tutor/student contact time decreases and teaching styles become less formal.

Current spatial requirements and an acknowledgment of unknown future requirements were the focus of our concept design for the Teaching and Learning Building at the University of Nottingham. We developed the form as a series of steel-framed modules which each provide adaptable column-free spaces that can be easily reconfigured by adding and removing internal partitions and loose furniture. Developing flexibility into the design during the early stages of a project enables easier implementation and increases the potential future benefits. Thus, the building can inherently respond to changes in learning as and when they occur without significant disruption to the length and cost of building works. In my opinion, flexibility is about carefully designing spaces to be easily altered to prolong their lifespan.

Developing adaptable buildings for future scenarios is not exclusive, nor should it be, to the higher education sector. As sustainability moves up the agenda, the commercial sector is now looking for more flexibility in office designs, reducing the likelihood of buildings being demolished entirely to be rebuilt in 30 years’ time. We are increasingly seeing clients looking for clean, open floorplates, high floor-to-ceiling heights, and spare capacity in MEP plant space, risers and ceiling voids to provide for any future tenant requirements for the space. As with higher education spaces, the focus is on designing buildings that provide a robust, future-proofed structural frame within which future users can shape their spaces to improve users’ quality of life, study and work.

As the recent temporary abandonment of university departments, libraries and workplaces in the wake of the coronavirus global pandemic shows, the future cannot always be predicted. As people across the world adapt their dining tables into workspaces and video conference calls negate the need for lecture theatres and meeting rooms, it is unclear what post-COVID higher education and office spaces require. As architects, ensuring our buildings are truly adaptable by integrating flexibility at the concept design stage is the best way to ensure they are equipped for future societal and building user changes.

The Teaching and Learning Building.

The Teaching and Learning Building.

The Teaching and Learning Building.

University of York masterplan model.

University of York masterplan model.

'Village green'-style workspaces at 1 Centenary Square. Photography Jack Hobhouse.

1 Centenary Square. Photography Jack Hobhouse.

Lively breakout space at the Big Data Institute.

Liam Bonnar

Data-driven design continues to shape our built environment and will increasingly influence how universities manage their estate assets. Make has been involved in a number of projects where empirical data has informed forecasting and capital planning for the coming decades. With the emergence of ‘big data’, the future of forecasting could be more dynamic, using real-time data from parameters like space utilisation, course popularity, attendance, funding and expected growth to predict future building needs. Universities could use these simulations to assess viability and build a case for demolition, refurbishment, rehousing or new construction – all before any design work has commenced.

As architects, it’s important to understand that our buildings will play host to a constantly churning set of spaces throughout their lifespan. Space requirements vary per faculty, from the incredibly specific – laboratories, archives – to general study spaces. There is no universal solution, but there are steps we can take to create flexible spaces. This means providing not only adaptable layouts but also the tools to support educational development.

Robust audio/visual infrastructure is one such tool, and can effectively bridge the gap between digital and physical university services. Students and staff can work from anywhere by connecting digitally or physically, and can also interact with the buildings themselves via localised environmental control, room booking, multimedia systems and even facility management.

Modern methods of construction (MMC), meanwhile, reduce waste and construction time while increasing quality. Common examples include prefabrication and modularisation, but we’re also seeing a trend in ‘design for disassembly’, where building elements are demountable, reusable and recyclable. By designing to a generous structural grid, with castellated beams above and raised access floors below to house services, demountable/modular partitions could be infinitely arranged.

Further flexibility could come from structural ‘soft spots’ in floors that accommodate new stairs or atria; bolted steelwork connections that allow for an adaptable structure; a reduction in fixed furnishings; perimeter cores and stairs that unencumber open-plan floorplates; and the relocation of energy-intensive building services like server rooms to purpose-built, off-site buildings to free up layouts and reduce plant. BIM is incredibly important here, as MMC relies heavily on coordination.

Flexible and adaptive buildings are key to creating resilience in the post-pandemic built environment. In a future where widespread adoption of remote working means learning can be experienced anywhere, education buildings need to work harder than ever to provide connected, flexible spaces that support social interaction, collaboration and community.

Urban Placemaking

How do you design city campuses to be of the city and not just in the city?

Greg Willis

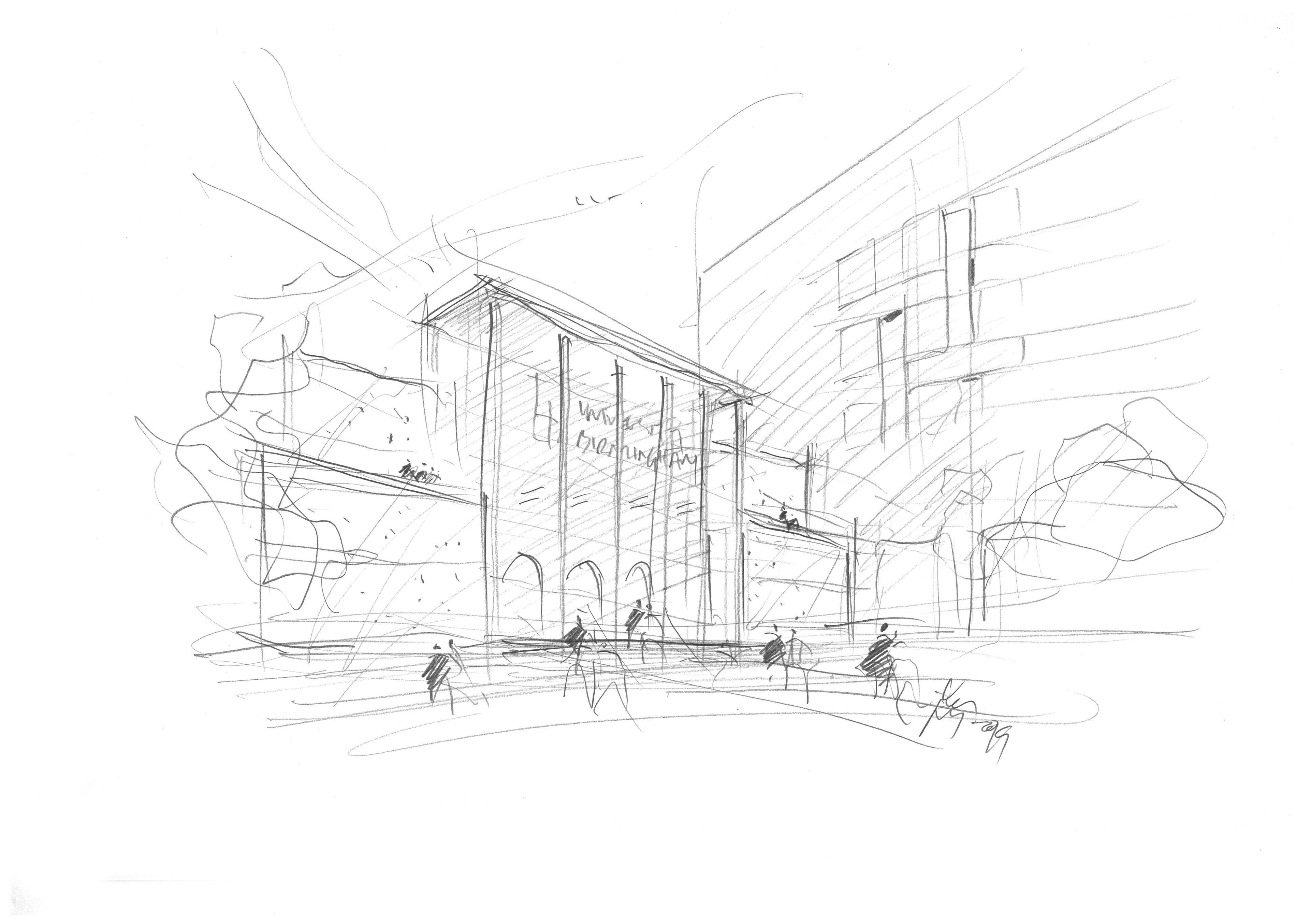

An interesting take on integrating campus and city came through our work for the University of Birmingham. The university wished to refurbish a key city centre site as a vital part of its own brand identity, which centres on “opening access and unlocking value so that others can follow and benefit.” This evolved into our core brief – to create a civic laboratory where great ideas and conversations inform research that matters and, in turn, inspire action that changes lives and communities for the better.

The University of Birmingham was born out of, and still operates within, a wider belief that the health, welfare and fairness of our urban societies rely on strong institutions that are connected to their communities. It is perhaps this sense of civic responsibility that is the key to healthy city and campus integration.

A civic university used to mean more than simply having a city centre site. Civic universities were built on key notions of endowment, opportunity, inclusion and legacy made possible through a genuine symbiotic relationship with local communities and the simple notion of wanting to give something back. Perhaps it is time to put the ‘civic’ back into these great institutions so that they may be more than simple academic silos. The stated intention of the University of Birmingham in its new city centre location is to reinvigorate this vision for the modern day by “utilising the University’s role as an anchor institution to bring together multiple stakeholders to address the challenges of our time and deliver inclusive growth for the wider region.”

Educational establishments within our cities are thus in a unique position to be able to open access and unlock value – and to do it all for the expressed benefit of others to follow. There are few institutions which can be so far-reaching and so forward-thinking in their mission, and therefore any building project should be equally as ambitious.

How do you design city campuses to be of the city and not just in the city? What should a modern civic university look like? The city must be welcoming to the university, and the university must be as representative as possible of the people in the city.

The Exchange – Sketch by Ken Shuttleworth.

The Exchange, University of Birmingham.

The Exchange, University of Birmingham.

RMIT New Academic Street. Photograph Tess Kelly Photography

RMIT New Academic Street. Photograph Tess Kelly Photography

RMIT New Academic Street. Photograph Tess Kelly Photography

Jennifer So

City campuses are in a unique position to not only provide their students with beautiful learning spaces but also look beyond and provide for the city they inhabit. Universities shouldn’t be designed to be inward-looking institutions but the reverse, with city campuses becoming part of the city fabric.

In Melbourne, RMIT’s New Academic Street is an excellent example of a city campus that is blended into the city block. With an urban civic focus as the design driver, the university has created a variety of different spaces for both the city and its students, including new gardens, laneways, rooftop terraces, retail and F&B. There are provide traditional learning spaces, but these are also supported with infrastructure for learning and collaboration. On the prominent corner of Swanston and Franklin Street is RMIT’s Media Portal, which actively engages with the city and brings its university activities into the public domain.

University campuses have the potential to provide informal learning spaces that can fill the void in our Australian city centres with genuine public space. In our CBDs, public spaces with workspace capabilities are more often than not leased or tenanted areas, and their use requires a paid drink or meal. True public space is often not free. Aside from providing public space, campuses can also add to the cultural landscape of the city, offering programmed events like industry talks, performances and even cultural exhibitions via a location that’s easily accessible and visible to the public. Universities will always be civic institutions. With beautiful spaces and an ambitious vision, urban campuses can become integral to any cityscape of the future.

Authors

Emma Thomas is a partner at Make and worked on the University of York masterplan. She was also part of the team that delivered the University of Nottingham’s Teaching and Learning Building, which secured multiple RIBA awards in 2019.

LinkLiam Bonnar is a partner at Make who helped deliver the Teaching and Learning Building for the University of Nottingham, and was part of our masterplanning team for the University of York. Liam is involved across various mentoring programmes, including RIBA Future Architects, FLUID Diversity and Open City.

LinkGreg Willis is a partner at Make and has led work with the University of Birmingham looking at the extension and conversion of heritage buildings. He has also been a guest critic at numerous architecture schools and is involved with the Future Spaces Foundation’s university programme for designing ‘Future Cities’.

LinkJennifer So worked at Make from 2016–2019 and contributed to our proposal for the University of Sydney masterplan.

Publication

This article appeared in Exchange Issue No. 3, a look at how the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced the future of university design, featuring insight from chancellors, architects, students and more.

Read more