Education Q&A

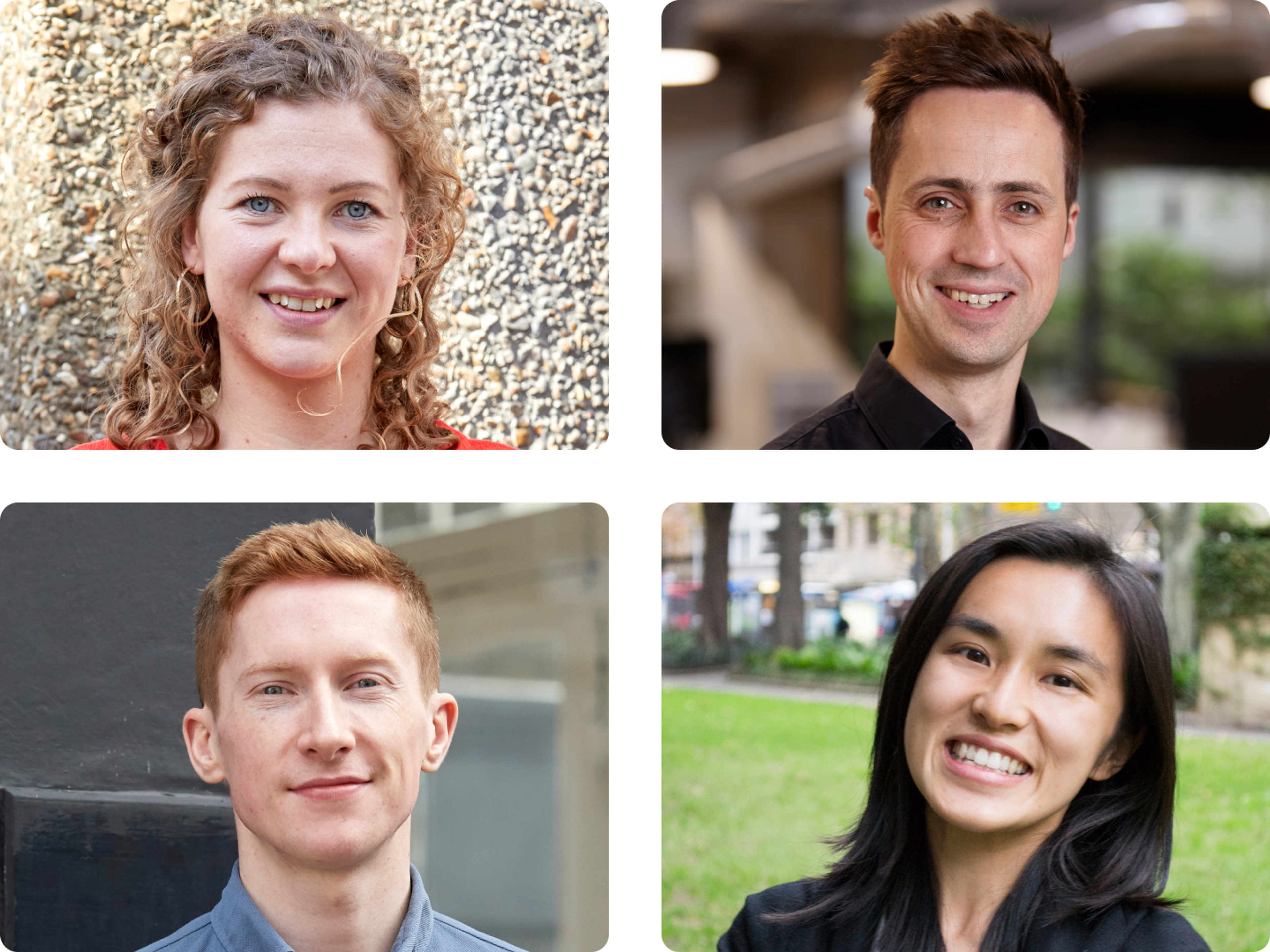

by Simon Lincoln, Nicole Marchhart and Victoria BoltonInterview with Nicole Marchhart and Victoria Bolton from the University of Sydney.

We discuss sustainability, the 2020 bushfires, and the impact of the pandemic on university design.

Nicole Marchhart (left) is the University of Sydney’s Energy and Waste Manager. Victoria Bolton (right) is the Design and Space Strategy Manager, UI.

Simon Lincoln: How has the University of Sydney pioneered the design of its buildings to minimise their impact on the environment?

Nicole Marchhart: Many years ago, we established a sustainability framework for the University of Sydney, similar to a Green Star-equivalent design standard. That framework ensured the design of all of our buildings incorporated sustainability features like solar power and water tanks for irrigation on gardens. Since then, we’ve moved towards a Green Star Design & As Built standard, which of course is a more universally recognised standard, and this will be adopted across all of our campuses. The Engineering Transformation Precinct will be the first of our new buildings to meet this standard.

We’ve also recently launched the University of Sydney Sustainability Strategy, which is the result of consultation with academics, operation staff and student representatives.

Victoria Bolton: Further to Nicole’s comments, it’s important to note the scale and age of our university. Founded in 1850, we have over 500 buildings across several campuses and properties, plus around 10,000 staff and 60,000 students. The Camperdown-Darlington Campus is our largest campus and through the Campus Improvement Program 2014–2020, we have invested A$1.5 billion in enhancing the built environment. Through the implementation of design standards, we have made product selection more sustainable.

The flow-on impact of the major builds has been a lot of relocations across campus. To create a more circular economy and reduce waste, we have implemented a furniture re-use store in partnership with Egans, which stores our high-quality furniture and redeploys it for other fit-outs. Thanks to this initiative, we saved around 18.5 tonnes of furniture from ending up in landfill in the first quarter of 2020.

NM: We’re enthusiastic proponents of training future generations by demonstrating how we can do things differently. Our Abercrombie Business School building is a wonderful example. That building was designed around a very large eucalyptus tree that provides habitat for local wildlife. By saving that tree, we’ve not only created a beautiful focal point for the design but, in my opinion, also positively impacted on the health and wellbeing of the staff and students who utilise that building.

Abercrombie Business School. Photograph Trevor Mein.

Abercrombie Business School. Photograph Trevor Mein.

SL: Can you share some of the pandemic’s likely long-term impacts on the university as both a workplace and a learning environment?

VB: My team manages the spatial register of the university. We capture where departments are located across our portfolio and monitor the utilisation of those buildings.

Looking ahead, our staff surveys are showing that most people wish to continue to work from home for two or three days a week. Suffice to say, that will impact the future of our workplace design. There will be a focus on why people come into the campus, and shifting the workplace design to suit those needs. Offices will still form part of the equation, but increasingly we are getting requests for more activity-based workplaces (ABW) which reflect the modern requirements. That is zones for quiet work, collaboration or connection. Our new Susan Wakil Health Building has all academics and staff in an ABW environment.

As you’d expect for any academic institution, one of the biggest pandemic challenges has been the change in education delivery. For example, at the end of last year, the Faculty of Science had only 18 courses online. Post-April 2020 they have over 240 wholly online. I must give credit to all the academics who made that possible and adapted their teaching to suit the new environment.

Post-pandemic, I don’t envisage us reverting to business as usual. However, when students and staff do return to campus in larger numbers, we will be challenged to create magnetic spaces they want to engage with. We must continue to ask ourselves: what is the genius loci of the university? I think a lot of that comes back to peer-to-peer learning and social connections. The university really provides a place to connect like-minded people within a space. Students in particular have been craving that. But it’s also about what’s in between the buildings and having spaces for informal learning, for dining, and for enjoying nature and the surrounds. I think our university is quite exceptional. It’s one of the most beautiful campuses in Australia and the world.

Over the past decade, we have prioritised designing buildings that focus on the ground plane. Our current design standards support an open ground plane to invite the public in, via a flow through of informal spaces that lead to formal spaces. But the pandemic sees us embracing more barriers to entry – for example, all of the buildings are on swipe access, so while you can look through the ground plane, it’s less seamless to navigate. The challenge is to foster an active ground plane while also maintaining a high level of security.

SL: What types of new opportunities might the post-pandemic landscape open up for universities in terms of the civic and social nature of campuses?

VB: I think we need to extend the conversation beyond our buildings and focus more on innovation districts. As per the 2016 Australian Innovation System Report, Australia is ranked 11th in the OECD for innovation, but [according to a 2015 Rattan Institute study] ranked last of 27/30 OECD countries for university-industry collaboration with large firms, and second to last for collaboration with small firms.

In my opinion, the solution lies in welcoming industry into our universities. How? By creating knowledge clusters that aim to solve the problems we’re facing in the 21st century. People who are driven to do innovative work will need to use existing facilities, because so many areas lack the capital to acquire new equipment or build new facilities.

Institutions like the University of Sydney already have the types of cutting-edge technology required to test innovative ideas, undertake research and development, and co-develop and co-design innovations that will drive society forward. The university’s Sydney Knowledge Hub (SKH) is a great example of this theory being put into practice. Located opposite our incubator start-up space Incubate, SKH provides a co-working space for start-ups, non-profits and corporates to come on campus and access our facilities and researchers. In addition, we have well-established companies like Microsoft on site, working with colleagues in the Sydney Nanoscience Hub. Other examples include Rio Tinto, GE and Qantas.

NM: I agree with Victoria and add that a university is a living lab, and we have a role to play to inspire change and incorporate sustainability research into design. Universities can demonstrate this sustainable and innovative design for student experience. In particular, the area of circular economy for ensuring products used are easily recycled at end of life and that buildings utilise materials that incorporate the circular economy, as raw resources are finite — an example of this is the work Dr Ali Abbas is doing, using crushed glass as a replacement for sand in concrete.

Sydney Knowledge Hub. Photograph Stephanie Zingsheim.

Sydney Knowledge Hub. Photograph Stephanie Zingsheim.

SL: What changes do you think we’ll see for university campuses as a result of Australia’s devastating bushfires in early 2020?

NM: Looking to the future, I think we’ll see more of a focus on precinct design and infrastructure that is more climate resilient. We need to consider not only how buildings impact on the land, but also how they impact on their neighbouring communities and the animals that inhabit nearby areas too.

From an infrastructure perspective, climatic events such as the bushfires really highlight the need for rigorous operational procedures and information mapping. For example, our School of Veterinary Science in Camden still required people to care for the livestock and maintain experiments during the fires. It was critical that our buildings had been zoned correctly, allowing parts of a building to be shut down that are not required during a period, while catering to specific key areas where essential equipment was located and was required to remain operational.

VB: The bushfires really amplified the students’ passionate appreciation for nature, biodiversity and the ways we interact with our environment. Specifically, they became vocal about recycling and environmental sustainability as exemplified by the Student Climate Strike in March. I thought it was wonderful to see their passion and sense of urgency to protect our resources and to reflect on the fact that we only have one world and one earth.

Authors

Simon Lincoln is the Asia-Pacific Make Director and oversees design and new business for the Sydney studio, which has included masterplanning for the University of Sydney and the University of Nottingham in the UK.

LinkNicole Marchhart is the University of Sydney’s Energy and Waste Manager, helping to deliver a sustainability framework across all campuses.

Victoria Bolton is the Design and Space Strategy Manager for the University of Sydney, looking at the implementation of design standards as part of a team.

Publication

This article appeared in Exchange Issue No. 3, a look at how the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced the future of university design, featuring insight from chancellors, architects, students and more.

Read more