Make retail roundtable

by Cara Bamford, James Chase, Katy Ghahremani, Peter Greaves, Grigor Grigorov, Jack Sallabank, Bill Webb and Sarah WorthWhat does the future hold for offline retail, and how is the evolution of the retail experience influencing how we design those spaces? Jack Sallabank chaired a roundtable with architects from Make’s London and Sydney studios to explore these questions and more.

Jack Sallabank: Are we seeing the death of offline retail?

Katy Ghahremani: No. I think it’s a misnomer to think about offline versus online shopping, because even people who shop online still have a relationship with the physical store. We are going through an evolution, and offline retail is no longer just a place where transactions happen. Instead it’s a place to build brands and consumer communities. I believe that offline retail has never been more important.

Peter Greaves: It’s an evolution, but it’s a forced evolution. The story of retail used to be about how convenience is king. Now there are better, more convenient ways to get stuff, so you need to be offered more to actually go somewhere.

Katy: Matches is an interesting story. It started off as a shop in Notting Hill Gate, and it became one of the first luxury shops to go online and in doing so became a massive online fashion retailer. Now it’s gone back to physical retail and has taken a townhouse in 5 Carlos Place. It has practically no stock, and it’s not about selling to you; it’s about creating a very curated service. If you want to buy anything, they still order it online. The retailers that understand the evolution of retail in the way Matches has are the ones that will remain relevant.

Cara Bamford: It’s about turning the shopping experience into an exhibition experience. I still want to feel the fabric on certain things. I want Debenhams to feel curated as opposed to a miserable, dour shop floor with things hung up unattractively.

Katy Ghahremani

Peter Greaves

Jack: What’s the story in Australia?

James Chase: Tip to top, Australia is three times the length of the UK, and the separation between communities is much greater than in the UK. Also, there isn’t the infrastructure in place, such as a strong postal service, to distribute goods and allow the likes of Amazon to build a business upon. As much as people want to be able to access things quickly, retailers in Australia can’t fulfil that via online, so instead they challenge themselves and improve their shopping experience.

Peter: It’s interesting that Amazon hasn’t worked in Australia based on that one thing, which is not being able to deliver everywhere fast. That’s all that online really offers – speed and convenience, which is only a small part of the retail experience.

Katy: I think we want to benefit from a range of retail experiences. We want fast, frictionless shopping for some things, but with others we want a really personal experience. At one extreme you have craft-makers selling via DM on Instagram. They don’t even have a website; you have to message them and have a conversation with the designer. We want all of it; it’s not an either/or.

Jack: As designers, how do you respond to this change?

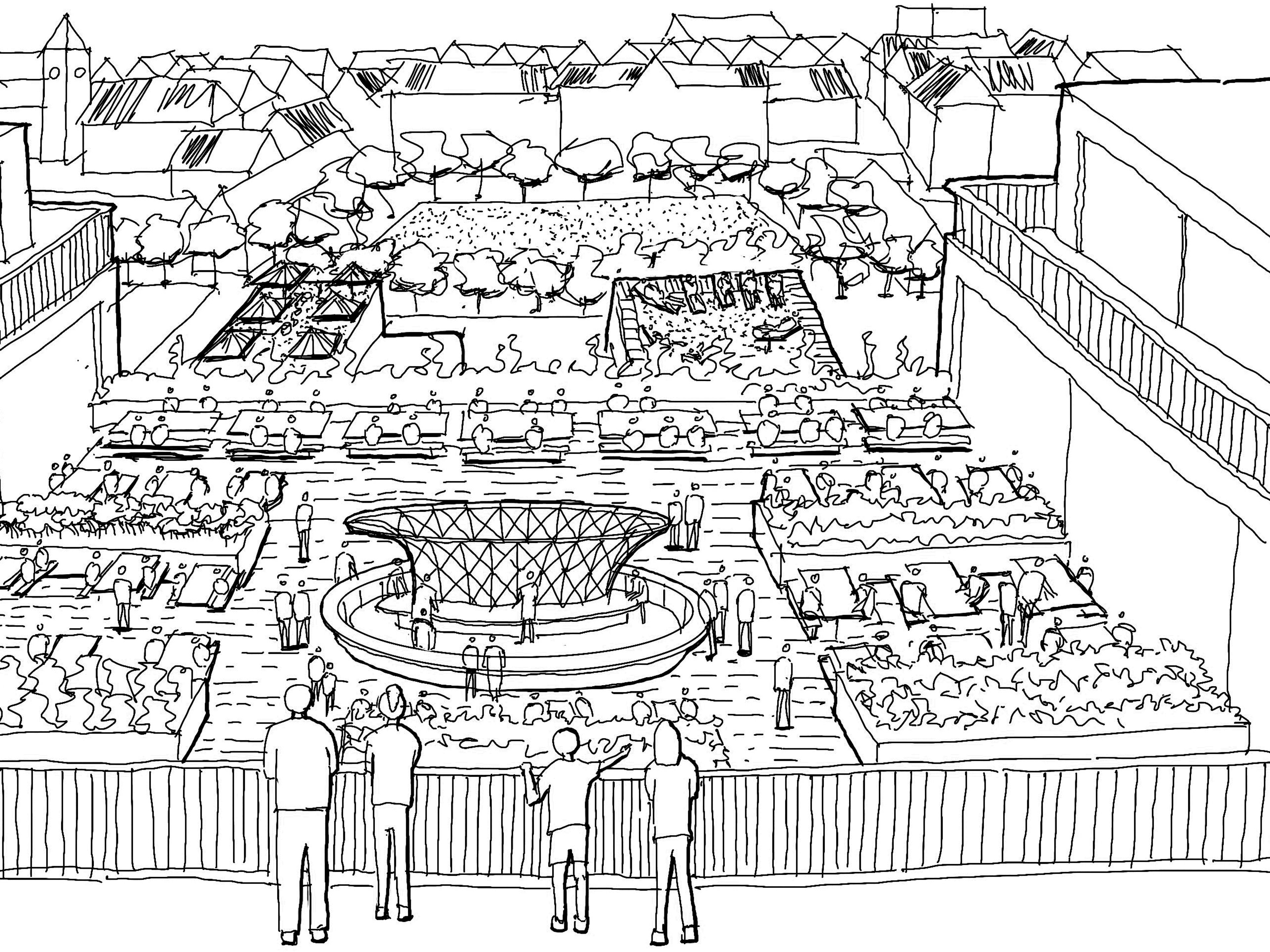

Bill Webb: It liberates you. In my opinion, the reason why many retailers fail is they have so much stuff. What happens if they get rid of all of that? You let light in, you can have gardens, you can get people to stay for longer. If you can actually get rid of the product, you can create much nicer spaces.

Katy: For us architects, it’s about making sure that spaces are designed to be as flexible as possible, because things are changing at such a pace that the best thing we can do from a sustainable development point of view is make sure we have enough head height and the column grid is right.

James: At bigger centres, individual tenants want the flexibility for further uses in their space, rather than a space just to sell a product. So, for example, they’re going to need additional plumbing, as in the next ten years they may want their own coffee bar added in the space. We’re building in that flexibility in the base build to future-proof their business and their future plans.

Grigor Grigorov: We’re often seeing cases where you have to adapt existing spaces, such as car parks or disused industrial sites that no longer fulfil their original purpose, into retail spaces. What’s important to us as designers is understanding how you can turn a car park that’s hardly occupied into a space that can take thousands of people at one time.

Grigor Grigorov

Bill Webb

Jack: How do we go about reimagining the UK high street?

Peter: Before the 1940s, high streets were mixes of civic uses, community uses and retail uses. People were going to these places to dwell and experience different things, and the retail was just one part of everything that was around. It’s not going to work anymore to have high streets that are solely retail destinations. Instead we should consider bringing in other civic uses and other community uses.

Bill: The high street should be about self-care and the things you can’t do online, such as hairdressers, skin care, nail bars, mental wellbeing, gyms. It seems to me that’s where the future of the high street lies. It ties in nicely with the idea of civic space and looking after the community, and it provides places where we can meet each other.

Katy: I think a lot of the retail closures represent stuff no one really wants anymore, so why are we mourning it? The fact that they’re going isn’t a bad thing. In commuter towns we’re seeing co-working spaces moving into empty retail spaces. This is a response to people being sick of commuting, and therefore we’re seeing the rise of the ‘metro-burb’. We need to think creatively about the uses of these spaces and make sure they’re place-specific.

James: When we talk to our clients, they want to bring experience back to a place because they want to bring people to the area and create a civic identity. The key is bringing people back to spend time together, and ultimately selling goods will come secondary to that.

Katy: We need to loosen up our planning uses on the ground floor. If a retail space has a gallery, a coffee shop and a workspace, what type of space is it? We shouldn’t be defining them. This is especially true for high streets. To allow high streets to evolve, we need to loosen up planning uses. Maybe we should have a use class that is actually about community and is not a specific use.

Bill: It’s worrying that we’ve let so much of our civic identity on the high street as a nation fall into retail. It used to be the place of the church or the army or these big institutions, and now we have a void that needs to be addressed.

Jack: One of the challenges for retailers and landlords is understanding consumer trends. What do you see as the trends they need to be aware of?

Bill: The way our approach to hobbies has changed. What people do outside work is now almost semi-professional. People have £10,000 bikes, and they go cycling every weekend. We have people at Make who make art, and they sell it, or they have their own website to sell jewellery. People don’t just want a Saturday spent in the pub; instead they’re doing a hobby that brings satisfaction.

James: In Australia people are wanting to find different activities other than the norm, and lots of those involve meeting people or doing things that you wouldn’t have done before. More often than not, things that historically wouldn’t have been cool are now cool.

Grigor: Everyone is building their own idea of themselves on social media. Everyone has an idea of who they are and what their story is, and retailers have to plug into that and help people build their story. What people do in their spare time is about fulfilling these personal goals and the image they see of themselves.

Katy: A behavioural change we are seeing is competitive socialising, like Bounce or Flight Club. This is aimed at the younger generation, who have possibly lost the art of conversation, and therefore meeting and gathering around an activity helps get that communication up and running.

Jack Sallabank

Cara Bamford

Jack: Who will be the future winners in offline retail?

Grigor: It will be the people who invest the time in understanding basic human needs and desires. That won’t always result in having to sell a particular type of product. It will be the brands that hit a particular spot in that time and space that the general public can relate to. So I would say it’s not about a particular type of store or space; it’s more about understanding what people want, who you are serving and how you meet their objectives.

Katy: The winners will be those who treat retail as a service or amenity.

Bill: Selling has always been about aspiration. What do you want to be? How do you want to be perceived? We’re going to help you be even closer to the people that you want to be. You used to aspire to have a big house and a big car; now it’s not that cool, and it’s about brands staying in line with what those aspirations are.

Cara: The winners will be those who can create places that get families in. It’s not just about creating spaces for the extremes or the tribes, but also places which are the middle ground and bring the family in.

James: Those mixed-use developers who can take a holistic approach and programme to different parts of their spaces will be the winners.

Peter: The village pub is almost a microcosm of a lot of the things that we’ve been talking about. It was somewhere you went to socialise and meet people. They had competitive socialising with drafts and pool and skittles. They animated the space with events such as band nights and quiz nights. The business model was about getting people in and ensuring they stayed for a while, because when they’re in they will spend money. That’s a small-scale example of what these new retail spaces need to be.

Tags

Authors

Cara Bamford, a Partner at Make, is working with clients on a range of mixed use and retail destinations from Make’s Sydney and London studios.

LinkJames Chase is a Make Partner working with Vicinity Centres in Sydney to see how a flagship centre can diversify its offering.

LinkKaty Ghahremani is a Director at Make. She oversees international architecture and interior design projects spanning many sectors, including hospitality and arts and culture.

LinkPeter Greaves, a Partner at Make’s London studio, works closely with the Future Spaces Foundation, an in-house think tank that explores how the built environment can positively impact on communities.

LinkGrigor Grigorov, a Partner in Make’s London studio, is project architect on Make’s portfolio of projects for Harrods. In 2018 he presented with Ralph Ardill at REVO on the future of shopping centres.

LinkJack Sallabank is the founder of Future Places Studio, a place-based research and strategy studio that specialises in exploring the macro and micro trends impacting the built environment.

Bill Webb, Partner at Make, has worked for the practice in both China and London, leading the design and delivery of several mixed use projects.

Sarah Worth is the Head of Communications at Make. She oversees corporate communications for all graphics, media and events, and leads Make’s Exchange thought leadership series.

LinkPublication

This article appeared in Exchange Issue No. 2, which explores the changing nature of the retail sector with contributions and design analysis from leading retailers, developers, consultants and more.

Read more