Harnessing data on the high street

by Alex McCullochThe British high street currently faces a number of challenges: business rates, the impact of online shopping, determining the role of a store, and Brexit. Underpinning them all is consumer behaviour and how it’s changing. At a recent CACI event, almost half of retailers and landlords identified this as their biggest business challenge.

According to the Office for National Statistics, in less than 30 years, 25% of the UK population will be over 65 years old. Should the UK maintain its current position as the country with the third-highest e-commerce sales (after China and South Korea), this shifting demographic should bring about far more integrated online behaviour. In other words, we expect the popularity of online shopping will only continue to grow.

Nonetheless, we know that the path to purchase is currently still a mix of online and offline engagement, and that 85% of UK consumer spend still ‘touches’ a store in some fashion, according to recent CACI research – whether that’s viewing the item first, collecting it or returning it. So stores remain important to shopping, but they need to differentiate themselves in ways that online shopping cannot, and must make themselves more relevant to the communities they serve if they want to stay alive and thrive.

Lewisham and Islington are both are inner-city London boroughs, but the former is home to less-affluent households, students and young professionals, while the latter has double the London average of what CACI calls ‘City Sophisticates’ – younger, well-educated, affluent city-dwellers. Yet many of the high street brands on offer in these two areas are the same, the store formats are the same, and even the stock is the same. Unsurprisingly, the retailers perform differently in each area, because they’ve not sufficiently taken demographics into account to stay relevant to their communities. And this is happening up and down the UK.

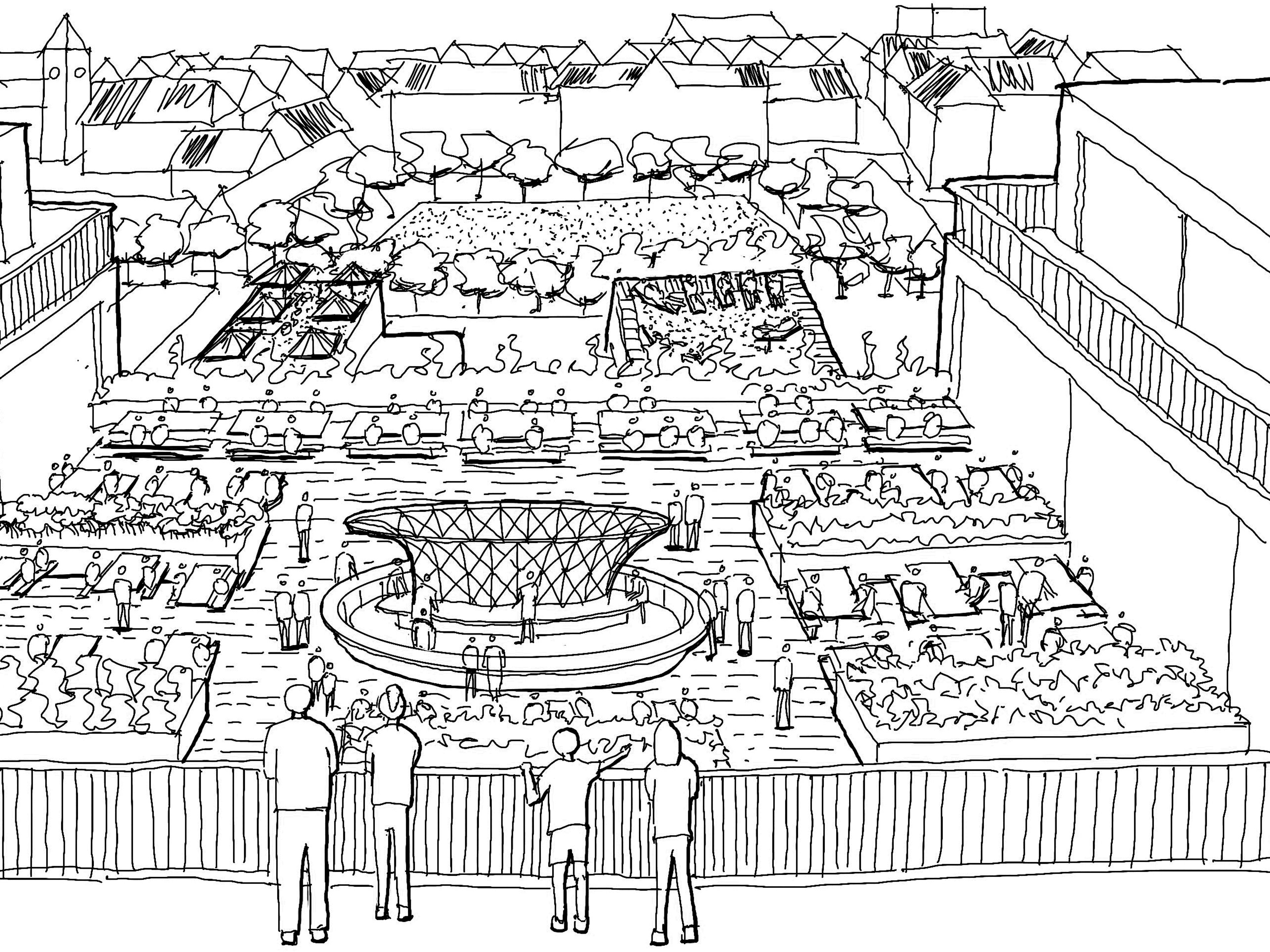

With this and the threat posed by online retail in mind, successful stores have begun to transform the role they play within their communities, gearing themselves towards a more hyper-local approach that aligns with the demands of the local population, rather than a one-size-fits-all strategy. Retailers that do this well are often independents, because they understand localism – they know their customers and understand what they want.

The question is: can big brands do the same? The answer is yes, of course – by using data. For example, CACI has developed tools like Acorn (demographic classification) and Location Dynamics (catchment information), and also harnesses mobile data. Waterstones, a UK book retailer with nearly 300 stores, tweaks store formats and has areas in stores dedicated to the local catchment. Likewise, IKEA creates different location-based store formats around London. Our data identifies why these formats work in these locations.

The data we’re able to offer now is vastly more in-depth than what used to be available. Historically, consumer data fell into two pots: micro/personal (eg, from focus groups, exit surveys and questionnaires) and macro/modelled research (eg, from the UK census, the Office for National Statistics and research firms). Now we can combine these methods with another layer of data generated by the two items a person almost always has on them: their phone and wallet. This information provides a whole host of new data sets, including beacons, wifi, apps, network credit, and debit and banking transactions, all of which can be used to answer key questions for owners and occupiers alike.

At CACI we use Location Dynamics mobile data in two different ways, allowing us to understand the catchment around a shopping centre, as well as the movement within the centre, across the UK and Europe. We code up with Acorn to understand the customer and always ensure GDPR compliance.

Greggs, the largest bakery chain in the UK, has eight stores in Leeds' city centre, but should all of them stock the very successful vegan sausage roll? By identifying the type of people most likely to adopt a vegan lifestyle – Acorn’s City Sophisticates, Career Climbers and Student Life – and then overlaying demographically coded mobile location data, we identified four of Greggs’ eight Leeds stores as having high populations of these groups around them. Mobile data can also be split by the time of day or week, and the potential consumer in and around the shop. This information can be used to create a more localised offering and store fit-out for a brand like Greggs, better connecting it to its customer.

When used well, data enables retailers to revive their position in the high street. However, it’s important to not lose sight of the question at the heart of your research, or the business challenge you’re trying to answer – and don’t underestimate the amount of analytics needed to do so. New data sets are exciting, but require GDPR best practice and data compliance, as well as heavy lifting on data analytics and bespoke software tools. And don’t forget that sometimes old-school methods are still best, depending on the question at hand. The data world today is complex; you need to navigate it and engage with it, but remember that new data is simply another tool, not a solution.

Tags

Authors

Alex McCulloch, Director of CACI, works with retailers and landlords to use data to inform future retail strategies.

Publication

This article appeared in Exchange Issue No. 2, which explores the changing nature of the retail sector with contributions and design analysis from leading retailers, developers, consultants and more.

Read more