Future of the high street

by Bill WebbAnother day, another bad news story for British retail. Whether it’s Borders or BHS, Maplin or Mothercare, we’re told daily that the industry is on its knees.

High streets in decline have a significant impact on the communities they serve.

London’s Upper Street is a thriving high street, bucking the national trend with its mix of chain and independent stores.

Walking around central Darlington, it’s easy to see the damage that can be done to a town’s civic identity by highly visible empty stores. Once-proud flagships on prominent sites are now boarded up – ghostly reminders of the power of debt. Living alongside these carcasses from the global economic crash of 2008 hasn’t done much to inspire Britons that the retail outlook is bright.

But are things that bad? It’s fantastic that groceries are delivered straight to our home, meaning Saturday afternoons can be spent in places other than the supermarket. It’s fantastic that streaming services let people living in even the most remote parts of the UK watch the latest international dramas. It’s fantastic that bus journeys can be spent choosing trainers and where to go on holiday.

From its earliest lifeform, retail has been where community happened. Trading is how cities were created, and retail was the environment where our communities happened, from markets to malls. Studies over the years have confirmed the role of the high street in particular as an important public space that promotes social inclusion and cohesion. It’s safe to say that its erosion is having a significant impact on our society, particularly as it occurs in tandem with the erosion of publicly provided public spaces like community centres, leaving a shortage of safe, dry spaces where citizens can escape the elements at little to no cost.

At the same time, though, large retail environments like Westfield are breaking down building mass to a scale that feels familiar to the user and creating far more movement between inside and outside. The appeal of their offer and subtle mimicry of the high street environment suggests that there may well be life in the high street yet.

Consumerism is changing, with a growing emphasis on wellbeing and self-optimisation over material ownership. This shift plays well for the high street, as looking after yourself still requires retail facilities with a physical presence – gyms, hairdressers, nail bars and dentists, for instance. Clustering these services, which require in-person transactions, continues to address certain metaphysical and psychological needs, like human interactions, connectivity and community. Also, food shopping is holding strong thanks to a renewed interest in farmers’ markets and their positive connotations of local, authentic exchange. While we want our cleaning products and household essentials delivered straight to our home, we still want to pick out something delicious for dinner and meet fellow shoppers excited by the range of items on display.

Thanks to global connectivity and social media’s role within that, we’re taking our non-work activities more seriously than in yesteryear. The internet lets us plug into niche communities, contribute to and comment on unique video content, and enjoy direct access to our heroes. Emboldened by this, we spend more time and energy on these pursuits, and are in need of places to indulge and enjoy them. The high street is well positioned to fulfil this need by being, at once, a physical presence – a place to share, meet and talk – and a platform for online sales and content.

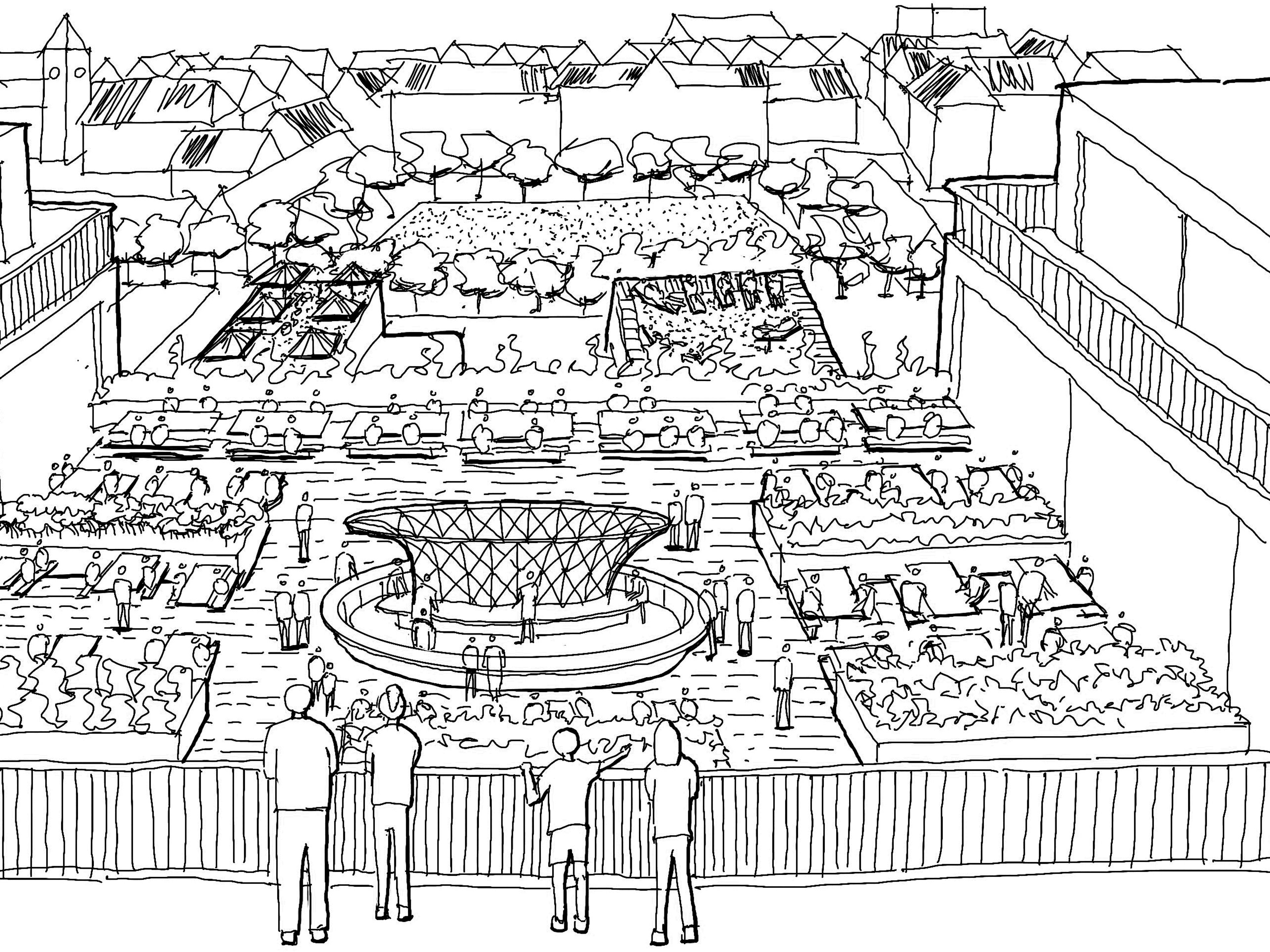

Localisation is currently playing out across many spheres, from politics to food. In this age of encroaching globalisation, demand is increasing for local industries that deliver home-grown products and services at a local point of sale. This trend, which signifies the growing crossover between traditional and experiential retail, presents a golden opportunity to reinstate the high street’s civic identity and put it back in the centre of the community.

Authors

Bill Webb, Partner at Make, has worked for the practice in both China and London, leading the design and delivery of several mixed use projects.

Publication

This article appeared in Exchange Issue No. 2, which explores the changing nature of the retail sector with contributions and design analysis from leading retailers, developers, consultants and more.

Read more