Bringing the brand to life

by Jack SallabankInstagram, Facebook and Twitter have given brands of all sizes the means to introduce consumers to their products while also enabling them to create a brand story that goes beyond the product. Pick a brand you like, check its Instagram account, and you’ll likely find a mix of product shots, aspirational lifestyle images and posts supporting social movements. Successful brands are expert at tapping into our ideologies and aspirations and presenting them in a way that makes us see the bits we like about ourselves in their brand. It’s clever, powerful and necessary for a brand to be able to do.

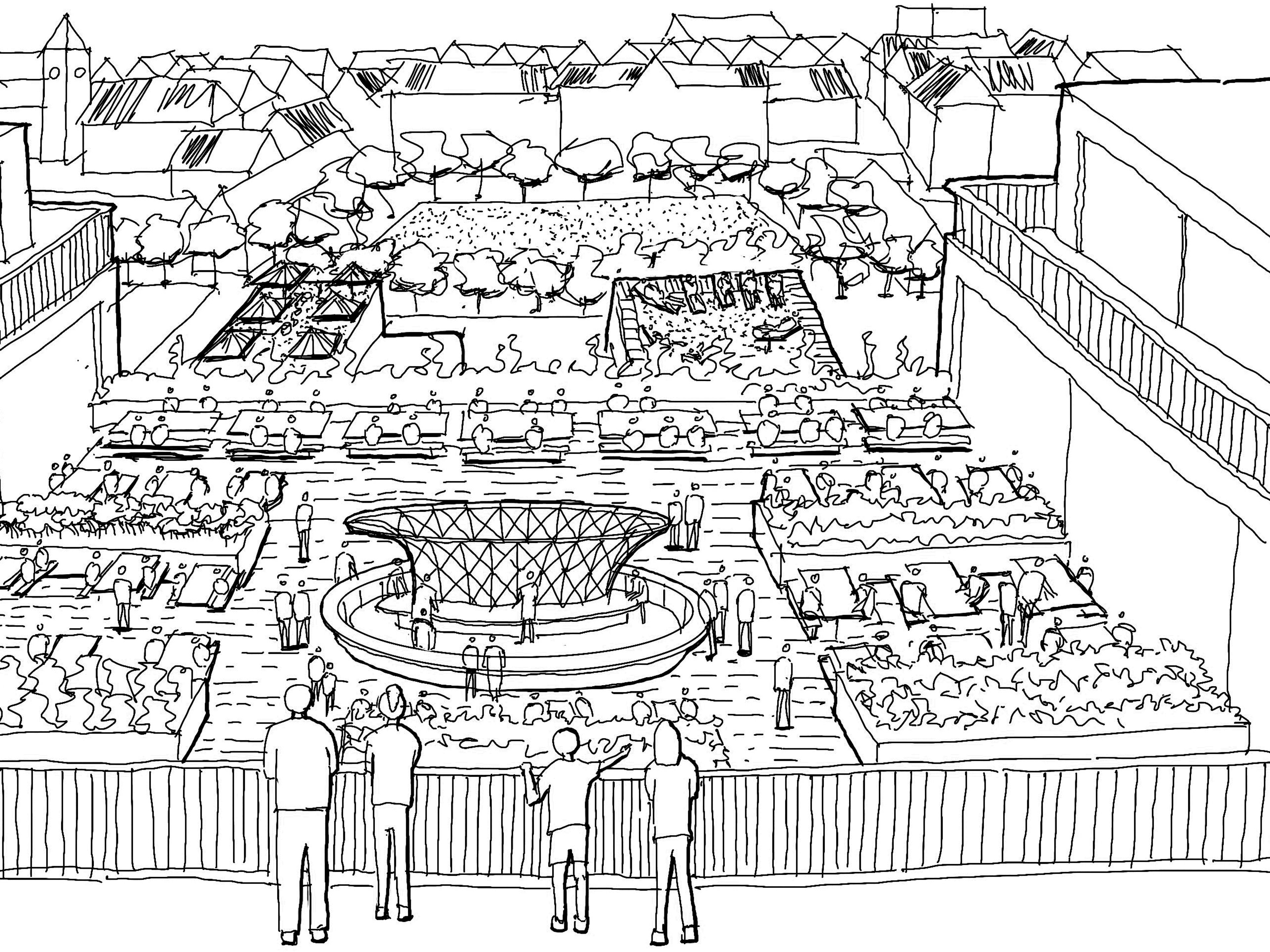

The challenge now facing these brands is how to replicate the engagement they’ve created through a screen into the real-life setting of a retail space. In an increasingly omni-channel retail world, no longer is social media the sole place for ‘likes’ or the sole place for stock. Instead, the physical space is now the place where a brand should be telling its story and creating a far deeper connection with the customer.

Reframing a space in this way will liberate brands to be more creative in how they design and programme a retail space, and in doing so will provide a far richer and more enjoyable retail experience. For larger brands like Nike or adidas, introducing out-of-hours activity in the space, such as DJ sets or TED Talks, is relatively easy to do. But for smaller brands or start-ups with limited space and budget and a smaller reach, the task of making their space do more than what it was originally intended for may seem a stretch too far.

I met up with two London-based entrepreneurs to learn about their businesses and how reprogramming their space has become a part of their brand identity.

Jake Hardy, Number Six.

The rear part of the store is used for range of events and collaborations.

NUMBER SIX

Having sold his e-commerce agency in 2012, Jake Hardy launched the men’s fashion retailer Number Six, which now has two physical stores in London, on Lamb’s Conduit Street and at The Old Truman Brewery in Shoreditch.

Jack Sallabank: Your core business is as a men’s fashion retailer, but you also use your space on Lamb’s Conduit Street for a range of events. How does the design of this space lend itself to this?

Jake Hardy: We have designed the space in such a way that we can contract and expand the shop when we want, which means we can free up space to do various activities. We put on pop-ups; we do collaborations with other brands; we do band T-shirt nights, sample sales, music nights. We sometimes rent out the space in the back during selling season, and that brand will also take an office downstairs, which helps make the space affordable for me.

JS: Why do you go to the trouble of doing events?

JH: Nowadays a brand like ours has to be more than a retail space, because of the level of competition. Events are about creating new audiences or sharing audiences with other brands that we like and introducing our customers to cool and interesting brands.

On Lamb’s Conduit Street there’s a great community among the different retailers, so we do lots of events in partnership with other retailers from the street. The events we run fit with our ethos, which is to have the best products and tell customers why we have the best. We will never try to sell to someone; we talk about the weather or whatever, but it will never be a hard sell. If we talk about the product, it will be to educate them, and then they can make their own mind up.

Events and collaborations bring in new audiences and visitors to the store.

JS: You have a digital background. How do you integrate digital and physical retail?

JH: We make sure digital is key to every bit of our business, online and offline. Nearly 50% of our sales are online, which is up from 20% a year ago. We have a mobile app, which is now 5% of our business. Of our online customers, 20% are click- and-collect.

We’re pretty good at using digital channels. We post across eight different social media platforms a minimum of once a day, which is to stay in people’s minds and drive traffic. We sell across channels such as Amazon, Depop and eBay. In the store we have screens up just behind the tills, and any content we create online will be on the screens in store. We data capture with the iPads in the store, and all receipts are email receipts.

JS: With the growth of your digital sales, do you see the brand always having a physical presence?

JH: We have two physical stores in London, and the growth of digital does make me ask if it’s sensible to have two retail spaces, especially as landlords are putting rents up. It’s a tricky decision to make, so we will have to see what happens.

Wander, a design-to-share restaurant in Stoke Newington, hosts a ceramics market once a month.

The space operates as a restaurant from Wednesday to Saturday.

Alexis Noble, Wander.

WANDER

Alexis Noble is the chef and owner of neighbourhood restaurant Wander on Stoke Newington High Street. Originally from Sydney, Alexis was a chef for 13 years before taking the plunge and opening her own place in London.

Jack Sallabank: Opening a restaurant in London can’t be an easy task. How did you find the experience of getting started?

Alexis Noble: The hardest thing about restaurants in London is finding an A3 premises, especially in Hackney. This was a Thai restaurant before I took it that had been abandoned for about a year and a half.

I didn’t have much money, so it was about working with what I have. I could always see the bare bones were good. It’s a very small space, but the high ceilings make it feel bigger than it is.

A lot of my friends thought I was crazy and I shouldn’t have done it, but when I saw it I felt it was a space that we could make into what I wanted. It took me six months to negotiate the lease. I opened on 8 November 2017, but I didn’t actually sign my lease until 25 November. It was so close to Christmas, and I just had to be open for Christmas.

JS: You describe this as a “Sydney restaurant.” What do you mean by that?

AN: At home there are way smaller places; here there are bigger restaurants with more investment, but if you don’t have a lot of money, you just make do with what you have, and then you try and grow.

The menu is designed to share, which is the type of food my friends and I would eat in Sydney, but for a smaller place doing sharing is actually a necessity. The kitchen is small; the pass is small; we don’t have hot lamps, and the limited amount of plates, glasses and cutlery we have means we have no option but to be a sharing restaurant. People criticise hipsters just creating more design-to-share restaurants, but actually it’s a far more economical way to do it. It’s more functional for kitchens to do sharing. You don’t have to put four plates up at once, so it’s also better quality.

JS: You operate as a restaurant from Wednesday to Saturday, and hold a ceramics market on the first Sunday of the month. Tell me about that.

AN: A lot of people come into the restaurant and really like the plates, but they don’t know where they can get them, so we have a market to help introduce them to some really creative talent, including the artists who made our plates. We put all of the chairs downstairs, push the tables back and set the space out as a ceramics market. Lots of people come, and the ceramists do really well. We’re closed on Sundays, and I like people to be able to use and benefit from the space.

JS: Is holding such events important to your business?

AN: The first six months was about getting open. Then it was about getting the business to stay open. Now that we’re 18 months in, we are sustainable and will always have guests, so I’m thinking about what to do now with the space. The common thing is that you must open five days a week as a restaurant, but why? What can I transform the space into when I am not here? I’ve thought about the space for freelancer creatives or as a café. We have a private dining room downstairs, but that could be used for wine tastings.

I’m a chef, so all of this is new to me. The ceramics market has been good for the brand and a different way to interact with customers. But it’s also been really lovely to do it with the girls who have made the ceramics, because they have all really helped me. It’s nice to work with people who understand the process of starting something and the self-doubt that you experience when opening a place.

Tags

Authors

Jack Sallabank is the founder of Future Places Studio, a place-based research and strategy studio that specialises in exploring the macro and micro trends impacting the built environment.

Alexis Noble is a Sydney-born chef and owner of neighbourhood restaurant Wander on London’s Stoke Newington High Street.

Jake Hardy, founder of Number Six, is a London-based entrepreneur who runs two retail spaces in the capital.

Publication

This article appeared in Exchange Issue No. 2, which explores the changing nature of the retail sector with contributions and design analysis from leading retailers, developers, consultants and more.

Read more