Future trends for urban labs

Page contents

The UK, like much of the world, is at an inflection point: the pandemic has forced us to reconsider fundamental questions about how our cities function and what they provide. According to CBRE, London office take-up in February 2021 was down 81% on the ten-year average. Conversely, availability rose to 73% above the ten-year average, with offices staying empty and occupiers considering how much space they will need in the future.

Retail’s struggles have also been well publicised, from the collapse of big names like Arcadia to landlords struggling to collect rent. Shopping has shifted online, and while undoubtedly a proportion of online retail spend will eventually return to bricks and mortar, how big that shift will be is unclear. Estates Gazette reported in December 2020 that across the UK, 975,000,000ft2 of retail and F&B leases signed since 2015 will expire by 2025. A staggering amount of retail space has an uncertain future.

That uncertainty is an opportunity to rethink the post-COVID future of our cities, reimagining the basic make-up of the built environment to match emerging trends such as the growth of the biotech market. In that way, changes brought by the pandemic can be viewed as a fresh start for cities looking to the future. With this in mind, we look at some of the future trends for urban labs which we expect to see in the coming years:

1. Retrofit and re-use

- Offices

With COVID-19 reshaping the office market, the pandemic could lead to a surplus in office space in our towns and cities. If so, it could be an opportunity to retrofit old office stock into labs. Pete Matcham at Make Architects argues that this could be a sustainable way to breathe new life into old buildings. Between London’s scarcity of space and a growing number of major office occupiers adopting some form of home working as standard policy, repurposing office stock is a prudent use of existing buildings.

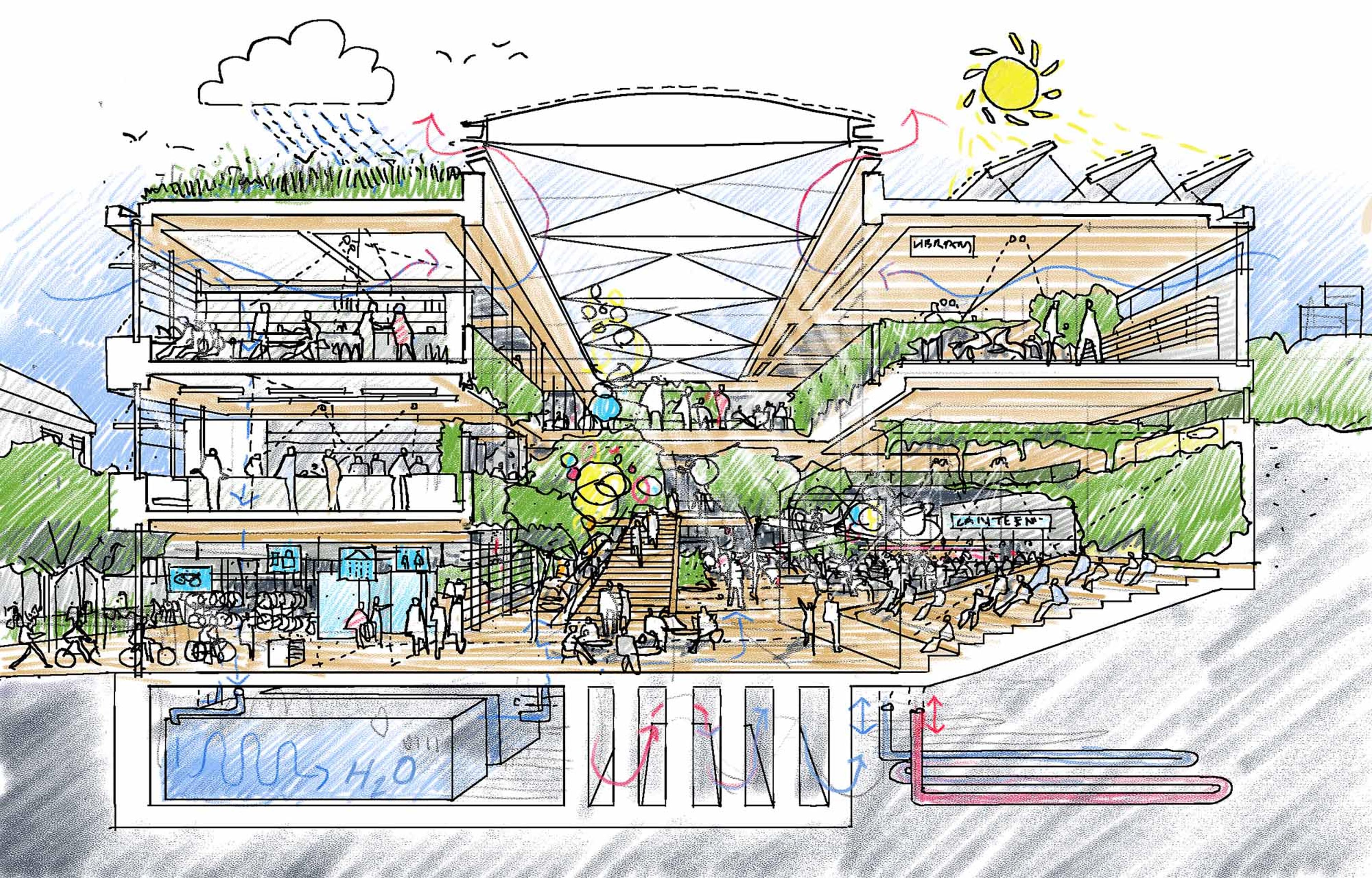

Sustainability – Drawing © Stuart Blower.

As explored in previous sections of this report, that comes with opportunities and challenges. The opportunity is to tap into a growing market where rents are considerably higher. A 20,000ft2 prime office in London would yield rental income of just over £2 million per year. A similar amount of high-end lab space could total £2.5 million in rent. The challenge for a building owner is determining whether the space they own can meet the requirements for lab space and whether the necessary retrofits are financially viable. The main areas to consider are floor-to-ceiling heights, structural limitations of the building, column spacing, and space for plant and MEP.

Jennifer DiMambro from Arup believes that organisations such as Arup and Make have an important role to play in advising landlords on whether their buildings are suitable for conversion into labs and, if so, how.

- High streets

The high street retail crisis pre-dates the pandemic, but as with other longer-term trends, lockdown has sped up the changes we’ve seen slowly growing for years. Footfall on London’s high streets in February 2021 was down 83% compared to pre-lockdown levels, figures from Centre for Cities show. Other major cities such as Birmingham and Manchester fared similarly, while areas with smaller office markets performed better. This suggests that city-centre high streets are most at risk if there is a sizable, long-term shift to remote working.

Scale Space, White City, London. Photo © Polly Tootal.

Scale Space, White City, London. Photo © Polly Tootal.

Labs offer an opportunity to breathe life back into these vulnerable high streets by reshaping their basic function. “We have high streets which aren’t going to be shops anymore,” said Charlie Mitchell from Scale Space. “The potential is in introducing anything from ‘light lab’ workshop space for tech companies all the way to high-spec labs for established life science firms.”

The introduction of the Class E use class in September 2020, which placed most commercial premises under a single classification, will simplify conversions from retail to lab space. Since planning applications are not needed for a change of use within a single use class, landlords will be able to make these changes with little difficulty.

2. Mixed use

Space constraints require the industry to think creatively about combining lab space with other uses. In London, we are already seeing the growth of ‘lab-enabled offices’ being introduced by the likes of Scale Space in White City and by Stanhope in the British Library extension. Indeed, ecosystems such as the one in King’s Cross demonstrate the interconnectedness and collaborative nature of science, which lends itself to space with multiple uses.

Addressing another urgent concern – a shortfall in housing – should inspire the industry to also consider the prospect of combining lab and residential space. This can be a real growth opportunity, Arup’s Jennifer DiMambro said, although it will require complex design to ensure that neither the residents nor the scientists in the building have to compromise with their space. One option would be to develop lab space on top of housing, which would keep the living space separate from the range of the machinery, MEP and extraction equipment required of labs.

Pete Matcham from Make identified some of the key considerations for designing lab/residential mixed-use spaces.

3. Changing user needs

Science is becoming ever more collaborative, and more collaboration has meant a change in how scientists use their space. Multidisciplinary teams have largely replaced individuals and small groups, and while different scientific disciplines will have their own requirements, they will all require more collaborative, workshop-style space.

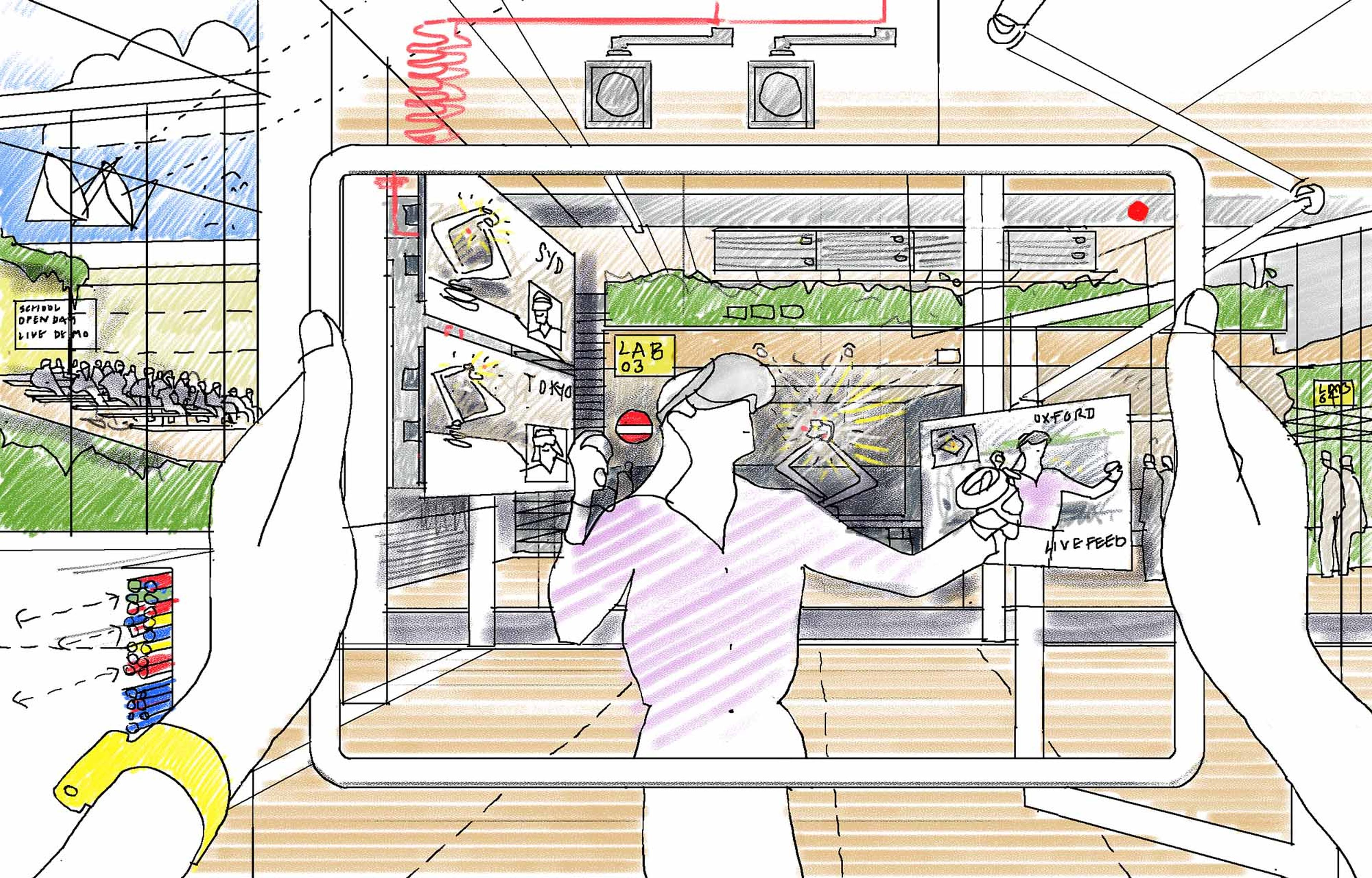

Tech and connectivity. Drawing © Stuart Blower.

At the same time, technological breakthroughs have allowed for, and even necessitated, greater flexibility. The rise of computational science has led to more automation and smaller equipment for analysis. The growth of 'in silico' studies (performed on a computer) has led to less demand for space compared to 'in vitro' (outside a living organism, like in test tubes) or 'in vivo' (in living organism) studies. Unencumbered by clunky equipment, labs can accommodate a mix of roles and teams. Although they are still complex compared to offices, this has simplified some of their fit-out requirements and will continue to do so in coming years. For real estate, this lowers the barrier to entry.

However, flexibility – whether that involves modular walls, movable desks or flexible equipment – must be incorporated to acknowledge that a substantial amount of individual work still goes on in labs.

4. Design innovations

The future of laboratory design has to start with flexibility. Looking at laboratories Make delivered over ten years ago, Pete Matcham says the key alterations by occupants over the years have been to upgrade and enhance their digital technology, whether to allow for more remote experiments, enable greater analysis or simply enhance connectivity. It is clear that the ability to retrofit space for new technology will be fundamental.

“It’s great to see that within our portfolio, the tenants have been able to adapt their space to accommodate their changing requirements without fundamentally altering the building structure. While research-driven buildings can’t be off the shelf, they can be designed with enough inherent adaptability to allow the building to flex according to the needs of its tenants, with inbuilt infrastructure to accommodate a range of requirements.”

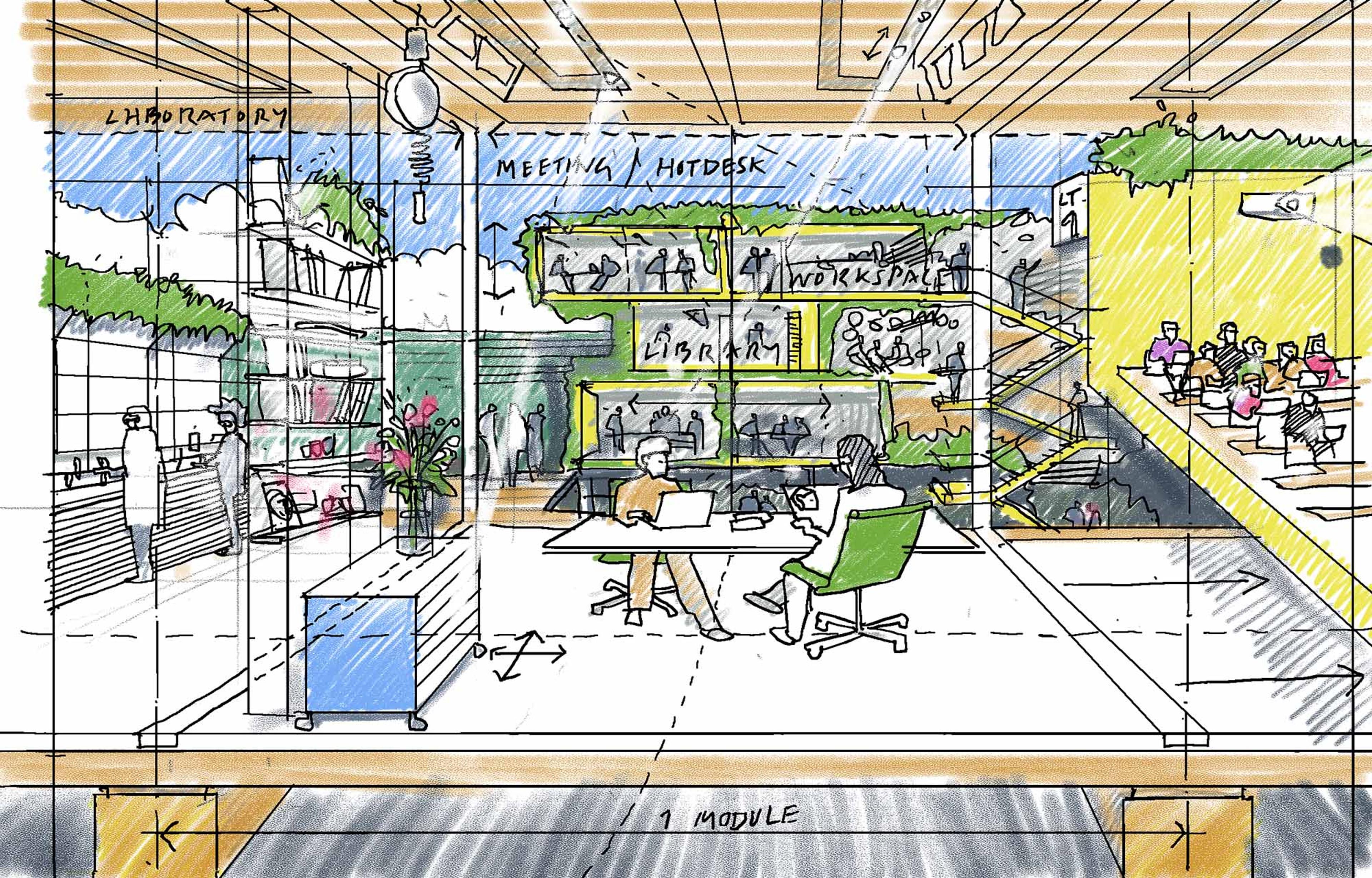

Adaptability. Drawing © Stuart Blower.

“When designing with a tenant in mind, it will be important to collaborate to predict power requirements and the variety of equipment, as well as deliver flexible space to cope with that change. This in itself will be a challenge to foresee, and it will be harder still for the speculative laboratory.”

Matcham also believes there will be a greater focus on integrating amenity and collaboration within the spaces. Current research-focused projects for Make are picking up on how the hospitality and workplace sectors are learning from each other. Indeed, Make is seeing some of that in client briefs – more space for workers to meet and discuss, a range of spaces for a range of working typologies, and, aligned with this, more amenity uses integrated within the building to attract and retain talent.

5. New locations

London has a blueprint for how ecosystems work in White City and King’s Cross. The next step is to consider where the biotech sector can grow beyond this. As the report has shown, these ecosystems grow around a research-driven anchor that draws in both companies and people.

Those interviewed suggested three growth areas: Whitechapel, anchored by Queen Mary University of London’s medical school; Stratford, anchored by UCL’s East campus; and Waterloo, with St Thomas’ Hospital. Over time, we can expect London to evolve as a series of science-based hubs, each with a slightly different focus.

If this does happen, we need to consider whether, in the short to medium-term, limiting lab development to these clusters will stifle London’s growth as a science hub. There is a finite amount of space in each of these areas, and limiting lab development to only them would overlook other places that otherwise have the potential to house them. However, the clusters individually have a greater opportunity to develop a critical mass that attracts talent. Given the quality of London’s transport infrastructure, the city is also well placed to bring new areas into play in the future. The hubs that exist now will eventually represent only the tip of the iceberg of what London has to offer.

6. Beyond London

The future growth of the biotech and life science market isn’t a story that will just play out in London, as Jennifer DiMambro from Arup noted, locations such as Manchester, Nottingham and Edinburgh are already doing some really interesting things in the world of life sciences, and we can expect to see that grow in the coming years.

Local governments up and down the UK are working in partnership with business, academia and developers to use the innovation district model to drive growth and inward investment. Such locations include Leeds, Belfast, Birmingham, Glasgow and Swansea.

A similar story is true globally. The Global Institute on Innovation Districts lists locations such as Adelaide (Australia), Monterrey (Mexico), Milan (Italy), Galway (Ireland) and Lyngby-Taarbaek (Denmark) among the innovation districts in their network.

7. The campus is dead; long live the campus

The future model for the life sciences and biotech market will gravitate towards urban locations, but this doesn’t spell the end of the campus model. Connectivity and walkability are synonymous with campus design, and both of these are key features of the innovation district model. Where the urban model will differ from the out-of-town science park model will be around the permeability and inclusivity of innovation-based locations.

In a recent report, Imperial College London stated that future innovation-based locations need to be “embedded in the communities which they aim to serve.” For such an aspiration to be achieved, the built environment sector needs to ensure that locations such as King’s Cross, White City and others that will follow are open, accessible and inviting to all.

8. Expertise

The industry needs to continue its learning journey, especially by looking at how the market has evolved in the US. The market there has real estate investment trusts dedicated to lab development, some of which, such as Alexandria Real Estate Equities, have nearly three decades of experience in the sector. Meanwhile, cities like Boston, which have world-renowned life science hubs and multi-sector developers, such as Related Beal, are as likely to develop housing as they are to develop state-of-the-art labs.

The sector is undoubtedly young in the UK, but it is growing; the likes of Scale Space, YOO Capital and Stanhope are among those leading the way. Outside London, Bruntwood and Legal & General’s joint venture with the University of Manchester, Bruntwood SciTech, is continually growing its regional science and tech presence.

These relatively early movers can be a blueprint for others in the industry – architects, developers and investors – to emulate and build on. This decade will be defined by biotech, and if London wants to not only keep up but also thrive and lead in the area, real estate must learn these lessons, step up and deliver groundbreaking innovative spaces.

Tags

Authors

Pete Matcham is a partner at Make who worked on the Big Data Institute and Innovation Building for the University of Oxford, on the Old Road Campus. He also acted as project architect for the London Academy in Edgware when he worked at Foster +Partners.

LinkPublication

This article appeared in White Paper: Urban Labs, a look at the real estate market for the UK's fast-growing biotech sector, with a focus on the commercial migration of labs to central London.

Read more